How the Epstein Files Actually Get Released

Sorry, but it’s not happening tomorrow.

I hate to be the guy who says this, but no—Congress isn’t about to crack open the Epstein files. Yes, there’s movement. Yes, there’s a petition. And yes, one new member just got sworn in who might finally tip the numbers.

But a vote? A release? Not yet. Not soon. Maybe not ever, depending on how this circus plays out.

Let’s start with the scoreboard

The House of Representatives has 435 seats. As of today, 433 are filled: 219 Republicans, 214 Democrats. The remaining two—Texas’s 18th and Tennessee’s 7th—are empty chairs waiting for special elections to wrap up. This afternoon, Adelita Grijalva of Arizona’s 7th took the oath to fill her late father’s seat, knocking the vacancy count down from three to two and tightening the partisan gap by a single body. That one new signature is being treated online like the crack of a starter’s pistol. It isn’t.

In Texas, the 18th District seat has been open since March, when Rep. Sylvester Turner died. The first round of the special election happened on November 4, with a runoff still to come. In Tennessee, Rep. Mark Green resigned back in July, and voters will pick his replacement on December 2. You can already guess the results: Texas 18 stays blue; Tennessee 7 stays red. Once both winners are seated, the headcount returns to the magic 435.

The House discharge petition

Now, the thing everyone’s talking about—the so-called silver bullet—is a discharge petition. Sounds dramatic, but it’s just a procedural crowbar. It lets a simple majority of House members—218—force a bill out of committee and onto the floor when leadership would rather keep it buried. It’s been used maybe a hundred times in the last century, and almost never works the first time.

Even when it does, the process moves like a DMV line on tranquilizers. First, the Clerk has to certify the signatures. Then the petition sits on the Discharge Calendar for 7 legislative days. Legislative days aren’t real days—they only exist when the House is in session, which means the Speaker controls the clock. After that, the Speaker gets two more legislative days to schedule the vote. So, if Mike Johnson decides to “run out the clock,” he just stops calling sessions, and the whole thing freezes. Legally tidy, politically toxic, perfectly normal.

The Senate

Let’s say—miracle of miracles—the petition survives all that and the House actually votes. That’s still only level one. The bill then shuffles over to the Senate, where 60 votes are usually required to dodge the filibuster. The odds of that many senators agreeing on the wording of a lunch order, let alone an Epstein disclosure bill, are roughly nil.

The President

But suppose lightning strikes twice, and it passes both chambers. The bill lands on the President’s desk. Yeah, that President. Under Article I, Section 7 of the Constitution, the President can sign it, veto it, or ignore it until it dies of neglect, which has the same effect as a veto. At that point, Congress needs a two-thirds majority in both the House and Senate to override—a political Mount Everest.

So yes, the discharge petition may have finally hit its 218th signature thanks to Grijalva. But that doesn’t mean a single file gets unsealed. It means the paperwork to maybe schedule a debate is now somewhere in the Clerk’s inbox.

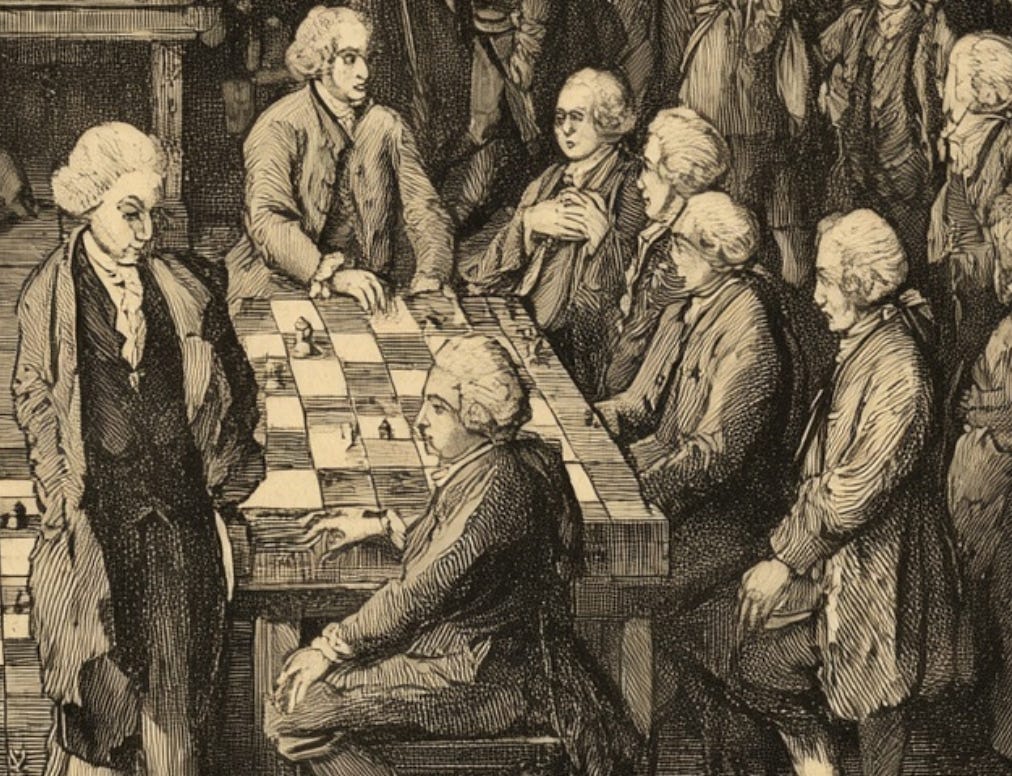

Slow-motion chess

That’s where we are: a slow-motion procedural chess match being mistaken online for the opening of the vault. It’s not the end, not the middle, and barely the beginning. What it does prove—again—is that Congress runs on calendars, not hashtags, and that the Constitution is less a lever than a maze.

If you came here hoping for fireworks, sorry. This isn’t Watergate. It’s a line of people waiting for the rules to do their thing. The Grijalva signature matters, but only the way one extra marble matters in a jar you still have to count by hand. Nothing moves until everything aligns: the petition, the Speaker, the Senate, and the President.

Until then, the Epstein files stay where they are—under lock, key, and the weight of 240 years of procedural molasses.